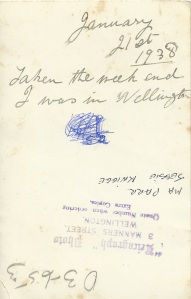

Last week I wrote about my friend E. and scanning old photographs to show her. Here’s a photograph I came across while I was doing this. I love the photo – two women, friends, stepping out in unison down Lambton Quay (in a larger version you can read the sign for Plimmer Steps) in 1938. (The date is on the back, along with the information that they were in Wellington for the weekend, explaining the small suitcases.) I wonder what they were looking at. They would have ridden from Ohakune on the train.The photo was taken by a street photographer.

My Grandmother, Jean Isobel Parr (née Donald) died when I was about twelve (1954). I remember I liked her, though she was known as “no nonsense.” I think I thought she was kind along with that. Sensible. You knew where you stood.

I found out as an adult that at the time she died she was losing mobility with bad knees and unable to continue to live alone with a coal range and an outdoor toilet. She took “heart pills.” It was being decided that she would have to come and live with us in Masterton: two girls and their parents in a two-bedroom state house. My parents would have had to put up a bed in the living room every night. I think my father was no longer working night shifts by then.

As my mother told it, she was called to Ohakune, via a phone message to my father’s workplace, because her mother was dying. She noticed an empty heart pills bottle on a shelf and asked where the pills were. The answer she got was, “I tipped them down the long drop.” Anything rather than be an imposition on her daughter and family.

I adapted this, along with some other more-or-less true tales, into a short story. It’s called “Family Saga,” and is in my ebook collection Stones Gathered Together. Sudden death has been a real theme in my family. As I have in a number of other ways over the years, I’m working on changing the pattern.