I’m doing this free, online, short course on Walt Whitman and his Leaves of Grass, led by Professor Elisa New of Harvard University. (https://courses.edx.org/courses/HarvardX/AI12.2x/2013)

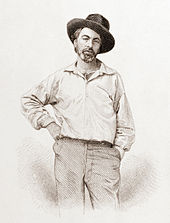

Walt Whitman (1819-1892), age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., 1855, steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison.

Leaves of Grass, for those not familiar with it, is a long poem, or collection of poems, that Whitman worked on over many decades during the second half of the nineteenth century. It’s an exuberant epic of a growing America, its body of people, the body of the writer and the places, urban and rural, that all inhabit.

A surprise, when I began reading in preparation for the beginning of the course, was the way he specifically includes women, as in, “And I will show of male and female that either is but the equal of the other.” This seems remarkable to me from a book that was first published in 1855. One other example:

I am the poet of the woman the same as the man.

And I say it is as great to be a woman as to be a man,

Although it goes on to refer to “the mother of men” women in these two lines are neither subsumed nor lesser.

Another surprise is the vehement enthusiasm he has for the physical world, the present and the future, humanity and his own body. (Wikepedia says, somewhat coyly, that “there is disagreement among biographers as to whether Whitman had actual sexual experiences with men.”) This is a poet who throws himself at and into the world and revels in his own body in ways that seem home-erotic to me.

In the fifty-second and final part of the poem “Song of Myself” is the line, “I sound my barbaric yawp over the the roofs of the world.” And nobody will, or does, stop and tame him, not in the lines of the poems, anyway.

I have not before come across a poet anything like Walt Whitman. I may have more to say about him.