First up, I never read Elizabeth Gilbert’s best-seller Eat, Pray, Love. She’s coming to Writers’ Week in Wellington, and her latest book, The Signature of All Things was in my birthday pile (yay!), so I’ve read that. I enjoyed it immensely, though it sagged a bit in the middle.

The protagonist, Alma Whittaker, is born into a wealthy family in Philadelphia, in 1800, not beautiful but clever. She becomes a botanist, then a student of mosses. The events and emotional traumas of her life, along with her study of mosses, lead her to an obsession with the connectedness (and brutality) of life. By the end of the book I was thinking that all the characters that impact on Alma have been invented by the author to demonstrate or illustrate that idea. (This is not a criticism.) I won’t say more about it as I’d have to give away too much of the plot. Suffice to say that I liked Alma a lot and most of the other characters, except for the man she married, Ambrose Pike, who I thoroughly disliked, which I suspect was not the author’s intention.

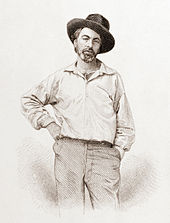

It is a coincidence that I read this book at the same time as I am exploring Walt Whitman’s long poem, Leaves of Grass, (as I wrote in my blog entry on 9 February). As I was reading The Signature of All Things, I kept think of the Whitman poem. There’s an exuberance and passion in Elizabeth Gilbert’s writing about the natural world in places that echoes Whitman, and some lists as Alma walks around Amsterdam that are very Whitmanesque. And Ambrose Pike embodies some of the more mystical and self-referential aspects of Whitman as he presents himself in the poems, though without the latter’s absorption in his physicality. (In fact, Ambrose Pike denies his body, especially in an erotic sense, in distinct contrast to Whitman.)

Alma herself has some Whitman-like qualities – she finds ways to enjoy her body in a world that thwarts her in this regard, but then she is a woman and not beautiful by the standards of her day. Alma also shares with Whitman a passion for engaging with the world and for knowing the world in the fullest possible way.

It may be fanciful to link Elizabeth Gilbert to Whitman, but it makes sense to me. And the exuberance is something I enjoyed in reading each of them.