For Sally.

The whole Emily Dickinson poem from which the title of this blog entry comes is here. Unlike some of her other, and some say better, poems on grief, it offers a little comfort. Kind of. Why I like the poem is that it suggests that all grief is grief (“They’re Water — equally —”), none diminishes or elevates another.

My daughter Helen died in January 1996. This week, on April 9, she would have turned fifty. I don’t know what to make of this. Who would she be at fifty? Would she have had children? Where in the world would she be living? How would we get on together? What relationship would she have with her brother? With my partner? These questions, and others like them, encapsulate my loss. So this is what becomes of raw, angry grief, this absence, this not-knowing, this Helen-shaped hole in my world.

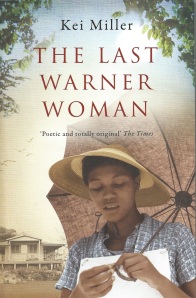

There’s nothing sentimental about loss, it’s a hard, sharp thing. And universal. In everyone’s life, sooner or later, one way or another. I’ve just finished reading Kei Miller’s The Last Warner Woman. Protagonist Adamine is born in a leper colony in Jamaica and her mother dies at the birth. And she is a warner woman, warning of impending disasters. When she goes to England – and what young person from Jamaica hasn’t gone somewhere? – warnings are understood as mental illness.

Adamine’s life is one loss after another, she even has to fight to keep her name, her birth having been accidentally registered using her mother’s name. She tells her story to Writer Man, who turns out to be … no, I’m not telling … and who ponders on stories and where they begin and what books are for and writes, “… here is the sad truth: Books end, and pages thin, and every word is pulling us towards that last, climactic full stop.”